When ADHD and Eating Disorders Overlap: Why It All Feels So Messy and What Could Help

ADHD and eating disorders often overlap in ways that many people do not expect. ADHD impacts body awareness, hunger cues, emotional regulation, and daily routines, which can make consistent eating patterns difficult. Over time, these everyday ADHD experiences can gradually shift into disordered eating or full eating disorder behaviors, especially when impulsivity, rejection sensitivity, or executive functioning struggles are part of the picture.

Research shows people with ADHD are significantly more likely to develop eating disorders, including anorexia, bulimia, and binge eating disorder. The blog explores how this connection forms, how eating disorders can take advantage of ADHD symptoms, and why understanding this link is essential for early support, compassionate treatment, and sustainable recovery.

Ever had days when your body feels like it’s speaking a language you don’t quite get? Your brain says “eat,” but your body stays silent. Or you plan to eat “later,” then suddenly it’s 8 p.m. and you’re starving, grabbing whatever’s easy. If you live with ADHD, this might sound familiar.

Living with ADHD can present unique challenges, and for some people, it may also intersect with disordered eating patterns. Understanding how ADHD symptoms, like impulsivity, inattentiveness, or difficulty with emotional regulation, can affect eating behaviors is an important step toward developing effective coping strategies and seeking support.

In this blog, we’ll explore the ways ADHD and eating disorders can overlap, highlight common patterns, and offer practical strategies for managing both. More than you might think, ADHD and disordered-eating or full eating-disorder patterns often show up together. For many people, it’s not about being “broken” or doing something wrong. It’s about how ADHD changes the way your brain, body, and emotions communicate with each other.

What ADHD Does to Body Awareness and Eating Patterns

First, I think it is important to get a clear understanding of how ADHD can impact body awareness and eating patterns. ADHD does not just affect focus or attention. It also influences the way a person notices internal cues, organizes daily routines, responds to emotions, and moves through their day. All of these pieces directly shape how someone experiences hunger, fullness, eating habits, and their connection to their body. While ADHD itself does not cause eating disorders, certain symptoms can increase vulnerability. Understanding this foundation makes it easier to see how certain ADHD traits can gradually shift into patterns that look or feel like disordered eating.

Hunger cues can get fuzzy

When you have ADHD, interoceptive awareness, tuning into subtle internal signals such as hunger, fullness, or body stress can be harder. Many people describe it like their internal antenna is turned down. They only notice hunger when it is very strong or when food happens to be nearby. This makes regular balanced eating difficult and can lead to cycles of ignoring hunger followed by overeating. Some research even suggests that people with ADHD may have more difficulty sensing what is happening inside their bodies, including hunger and fullness cues.

Executive functioning makes meal planning difficult

Cooking a nutritious meal involves many steps. You have to remember to shop, choose what to make, prep ingredients, cook, and clean up. For people with ADHD, that chain of tasks can feel overwhelming. Skipping meals, relying on convenience foods, or eating only when something quick is available becomes more of a survival strategy than a choice. This kind of irregular eating rhythm often overlaps with disordered eating patterns.

Impulsivity and the brain's reward system create challenges

ADHD often comes with a brain that searches for quick reward. Food, especially sugary or high energy foods, can give a fast boost. That makes impulsive or binge type eating more likely for some people. Emotional triggers such as stress, shame, or loneliness can also blend with impulsivity and low self regulation. When food becomes one of the only ways to soothe or get quick relief, the pattern becomes harder to break.

Sensitive emotions and a fear of rejection add another layer

Many people with ADHD experience intense emotional discomfort when they feel criticized or rejected. This can lead to restrictive eating, secretive bingeing, or feeling stuck in cycles of shame. When shame becomes part of the eating pattern, healing becomes more complicated because the struggle is often about deeper emotional pain, not just food.

What the Research Says:

A large meta-analysis found people with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) are about 3.8 times more likely to be diagnosed with an eating disorder (ED) compared with people without ADHD. PubMed

Within that same analysis, the increased risk held across different ED diagnoses: about 4.3 times higher for Anorexia Nervosa (AN), 5.7 times higher for Bulimia Nervosa (BN), and 4.1 times higher for Binge Eating Disorder (BED). PubMed

In a matched cohort study of children and adolescents with ADHD, 31.43% screened “at risk” for an eating disorder (via EAT-26), compared with 12.14% of matched controls without ADHD, showing a notably higher risk in youth. pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov+1

Community-based research among adolescents found that those with ADHD symptoms had significantly higher rates of disordered-eating behaviors compared to their peers without ADHD, supporting that this overlap is not limited to clinical or treatment-seeking samples. However, it is also worth noting when researchers adjusted for other factors (anxiety, substance use, etc.), the strength of the association lessened. PubMed+1

The mechanisms (why/ how) are still under investigation. Shared genetics, neurobiological reward pathways (dopamine), executive‑function challenges, emotional regulation, interoceptive awareness all play possible roles. PubMed+2ScienceDirect+

Taken together, these findings make a strong case that ADHD significantly increases the likelihood of disordered eating or a full eating disorder, well beyond what would be expected by random chance.

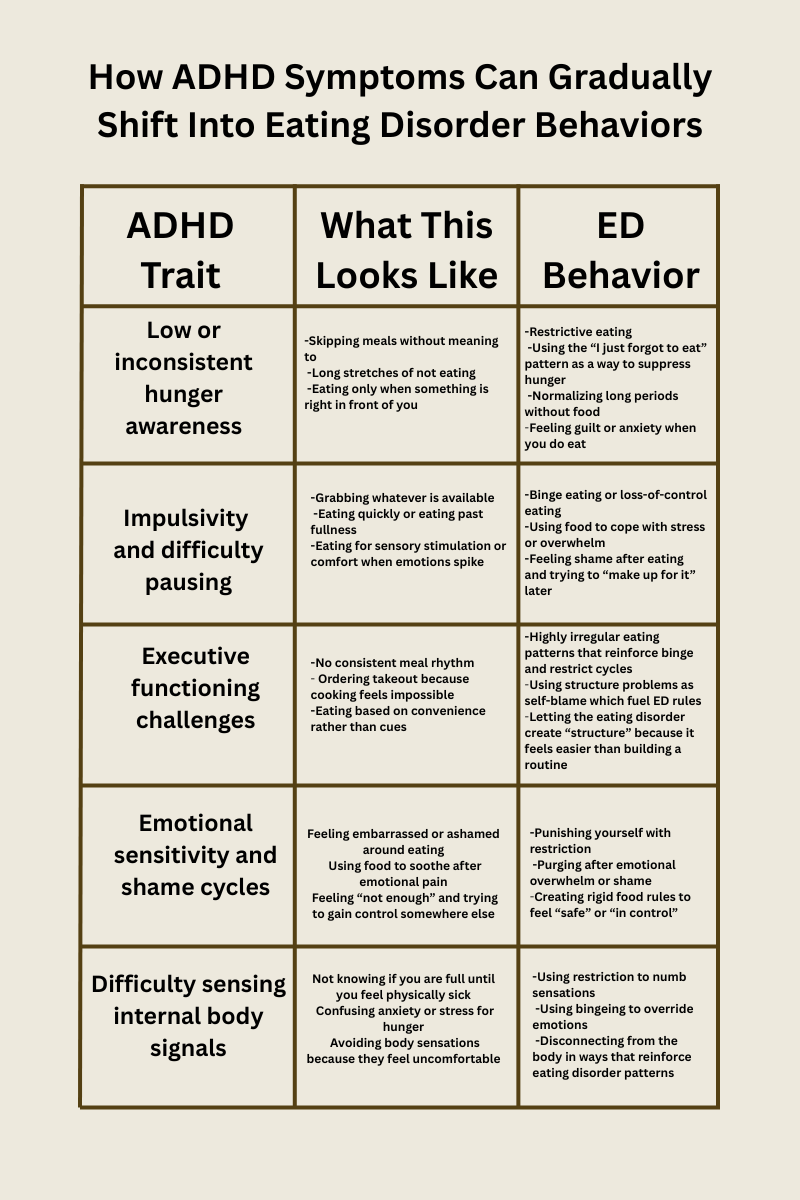

How ADHD Symptoms Can Gradually Shift Into Eating Disorder Behaviors

Eating disorders do not usually show up suddenly. Instead they often grow from patterns that begin as ADHD traits coping strategies or moments of overwhelm. Over time those same patterns can shift into something more rigid or more painful.

Below is a gentle map of how this progression can happen.

Need for stimulation or reward

Another factor to consider is that a person with ADHD may move toward foods that offer quick pleasure when bored or seeking comfort.

Over time ED behaviors can take advantage of this by using food for emotional regulation or using restriction for emotional numbness creating rigid patterns that are hard to escape.

This progression does not happen because someone chooses an eating disorder. It happens because ADHD traits create vulnerabilities that eating disorders latch onto.

Nuances: The Spectrum of Eating-Related Experiences

It’s important to recognize that the relationship between ADHD and eating behaviors exists on a spectrum—there’s no single experience that applies to everyone. Some individuals may struggle with binge eating or emotional eating, where impulsivity and difficulty regulating emotions play a role. Others may experience restrictive or selective eating, sometimes linked to sensory sensitivities or challenges with interoceptive awareness (not noticing hunger or fullness).

Examples of eating-related patterns seen in people with ADHD may include:

Binge eating or emotional eating in response to stress or impulsivity

Restrictive eating due to sensory sensitivities or routine disruptions

Irregular or missed meals from inattention or executive-function challenges

Selective eating patterns, sometimes overlapping with ARFID

Additionally, eating patterns can fluctuate over time, depending on stress, routine, sleep, or co-occurring conditions such as anxiety or depression. ADHD symptoms may amplify certain behaviors at some points in life and less so at others.

Research supports that ADHD symptoms can contribute to a variety of eating patterns, but experiences vary widely among individuals.

Understanding this variability helps to avoid overgeneralization, validates diverse experiences, and emphasizes that individualized strategies, rather than one-size-fits-all approaches, are most effective for supporting both ADHD management and healthy eating behaviors.

What about ARFID?

Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID) and ADHD often overlap because both involve sensory sensitivities, low interoceptive awareness, and executive functioning challenges. For many with ADHD, textures, smells, or temperatures can feel overwhelming, while irregular hunger cues or difficulty trying new foods make eating harder. This combination can contribute to restrictive patterns that go beyond “picky eating.”

When Eating Disorders Take Advantage of ADHD Symptoms

This is one of the most important pieces people often do not get told. Eating disorders frequently build themselves around the exact symptoms that make ADHD difficult.

If you are forgetful, the eating disorder uses that to push restriction.

If emotions hit hard, the eating disorder offers bingeing or purging as a release.

If planning meals feels impossible, the eating disorder steps in with rigid rules.

It becomes surprisingly easy to mistake an eating disorder pattern for an ADHD quirk. And once those wires get crossed, untangling them requires compassion and clarity.

Why This Matters

Understanding the overlap between ADHD and eating disorders helps us see that for many people, disordered eating is not just about food. It is about brain wiring, emotional experiences, body awareness, and the rhythm of daily life.

This means:

Early screening is important for anyone with ADHD experiencing eating challenges.

Treatment should consider both ADHD and eating behaviors, not just one.

Recovery is possible with structure, emotional support, and ADHD friendly strategies.

Quick Takeaways: ADHD & Eating Disorders

People with ADHD are at higher risk for disordered eating, especially binge eating or bulimia, but not everyone with ADHD will experience these challenges. In fact, many people with ADHD will not experience an eating disorder.

Traits like impulsivity, inattention, emotional regulation difficulties, and sensory sensitivities can influence eating patterns.

The exact reasons ADHD and eating disorders overlap aren’t fully understood; likely factors include brain reward pathways, executive-function differences, and awareness of internal cues.

Individual experiences vary, so personalized support and treatment addressing both ADHD and eating behaviors is key.

References:

Instanes, J. T., Klungsoyr, K., Halmøy, A., Fasmer, O. B., & Haavik, J. (2016). The risk of eating disorders comorbid with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 49(10), 1045–1057. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27859581/

Jahrami, H., AlAnsari, A. M., Janahi, A. I., Janahi, A. K., Darraj, L. R., & Faris, M. (2021). The risk of eating disorders among children and adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: Results of a matched cohort study. International Journal of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 8(2), 102–106. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8144858/

Cortese, S., & Vincenzi, B. (2017). Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms and psychological comorbidity in eating disorder patients. Psychiatry Research, 254, 70–76. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28534123/

Nazar, B. P. D., Morales-Alvarez, C., & Newlove-Delgado, T. (2017). Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder and eating disorders across the lifespan: A systematic review of the literature. European Psychiatry, 45, 27–36. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27693587/

Nobis, M., Laghi, F., Brunetti, C., Cabaleiro, L., Hernández-Martínez, C., & Jansen, A. (2022). The association between eating disorders and mental health: An umbrella review. Journal of Eating Disorders, 10, Article 132. https://jeatdisord.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40337-022-00725-4

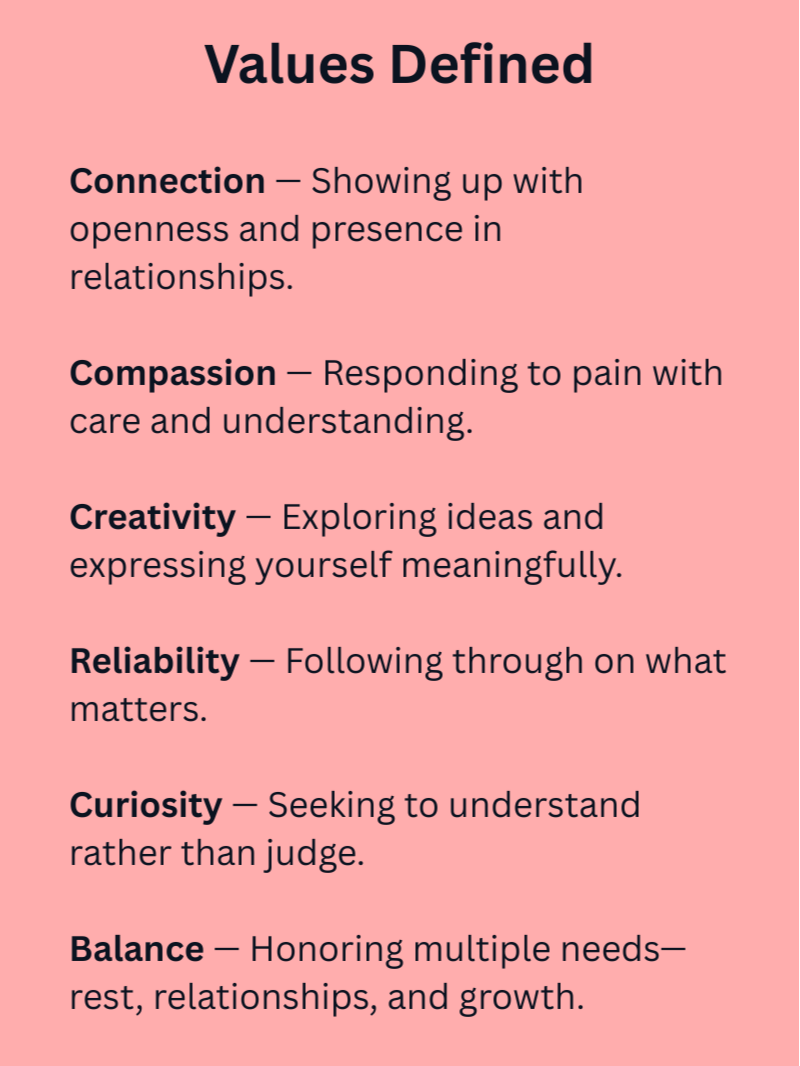

Values: Your Inner Compass

Life can feel messy and unpredictable, leaving us unsure of which direction to take. This post explores how values act as a personal compass, guiding your decisions, clarifying priorities, and helping you live intentionally. Learn how to define your values in your own words, identify your core values, understand the messages behind your emotions, and take practical steps toward a values-aligned life.

Life can feel unpredictable, messy, and full of moments that leave us wondering what direction to take next. You might feel like you’re doing all the “right” things and still end up unsure, overwhelmed, or disconnected from the life you imagined for yourself. That doesn’t mean you’ve failed. More often, it means you’re trying to steer without a compass.

That compass is your values.

Values are the guiding principles that help us choose how to move through the world. They give our days direction and our choices meaning. When we understand our values, we begin to understand ourselves not just who we are, but the kind of person we want to become.

If you read our previous article on living with intention you might remember the image of being in a boat without a paddle, just drifting wherever the current takes you. That metaphor still rings true here. When you know your values, you pick up the paddle. You steer. And what we’re unpacking now is how to know which way you want to steer, by clarifying your values, understanding the messages your emotions send, aligning goals behind what matters, and choosing to live more intentionally.

What Are Values?

Values are the qualities, ways of being, or themes that matter deeply to us. They aren’t rules or expectations, and they’re not about what other people say should be important. Think of them more like the wind that fills your sails. They help create a steady source of motivation and direction that helps you move toward a meaningful life.

Someone may value creativity, while another values reliability, play, compassion, or adventure. You might care deeply about curiosity in your work and connection in your closest relationships. None of these are right or wrong; they simply reflect what matters most to you.

Values are ongoing. You never “finish” kindness or integrity. They’re not tasks you check off a list, they’re qualities you practice, again and again. Goals can be completed; values stay with you, guiding how you show up each day.

Something that often gets missed in conversations about values is how personal they are. Two people can share the same value, yet define and live it in totally different ways. For example, someone who values connection may think of regular phone calls with loved ones, while another expresses that same value through hosting dinners, quality time, or simply being fully present during conversations. Neither is “more right” they’re just different interpretations of the same core value.

That’s why it’s so important to define your values in your own words. Without that clarity, it’s easy to get pulled into what you think a value “should” look like rather than staying true to what feels most authentic. When you understand what a value means to you, it becomes easier to notice when you’re living it, when you’ve drifted from it, and how you might lean into it more intentionally.

Why Values Can Feel Confusing

In my work with clients, I often hear people say they “know” their values. And in a broad sense, many do. They may identify with a long list of ideas such as honesty, family, creativity, balance, or achievement. However when we begin exploring more deeply, people are often unsure which values are their core values and which are simply qualities they feel they should care about.

This confusion makes a lot of sense. Most of us were never taught how to define our values, let alone how to organize them. When you look at a long list, it’s easy to assume all values should be equally important. But that belief can leave us overwhelmed and stuck.

We cannot actively embody all values all the time. It’s simply not possible. Trying to honor every value at once can create pressure rather than clarity. Instead of guiding us, values begin to feel like another task list we’re constantly failing to complete.

Clarifying which values are central in your life allows you to make choices with more ease. It doesn’t mean you ignore everything else; it just means you are choosing direction based on what is most important in this season of life. Naming a smaller set of core values allows you to move with intention rather than getting pulled in every direction at once.

How Emotions Help Us Understand Our Values

Our emotions can be some of the clearest signals of what matters to us, almost like a built-in notification system. When a feeling shows up (especially the uncomfortable ones), it’s often pointing toward a value that was touched, threatened, or honored.

Guilt is a common example. It doesn’t always mean you did something “wrong.” Sometimes guilt simply shows up when we’ve stepped away from something that feels important. If someone tells a lie and immediately feels unsettled, that reaction may be their internal signal that honesty is a value they want to live by.

Emotions can also show up when two values pull in different directions. Think about a moment where you’ve had to cancel plans with a friend because a family need came up. You honored your value around family, but guilt may still surface because dependability or commitment also matters to you. Both values are valid, your emotions are just reflecting the tension between them.

Even more subtle feelings can highlight what we care about. Sadness after a friend moves away can show how much connection matters. Frustration in an unfair situation can highlight a strong value around justice or respect. Anxiety may reveal a desire for stability, clarity, or safety.

Emotions aren’t always comfortable, but they’re meaningful. When we treat them as information instead of problems, they can help us identify which values are asking for attention and guide us back toward what feels aligned.

Finding Your Core Values

Knowing your values is one thing. Knowing which ones are your core values, the ones that truly guide your decisions and give your life direction, is another. Many people have a long list of values, however they often get stuck on how to narrow that list it down to the few values that really matter most.

A practical approach is to look for patterns in your choices over time.

When tough decisions arise:

-Which principles consistently guide you?

-Which values are non-negotiable?

These repeated priorities are usually your core values.

It’s also helpful to consider your motivations behind your goals and actions. Ask yourself: Why does this matter to me? If your answer connects to a deeper principle, that principle may be one of your core values.

Your core values are the ones that persist, even when life gets complicated.

Putting Values Into Action

Knowing your values is helpful, but the real change happens when you begin using them to guide how you live. This doesn’t have to involve sweeping life changes. Small steps can be incredibly meaningful.

Someone who values growth might begin trying new things, even if they feel unsure or awkward. A person who values connection might send a message to someone they care about. Someone who values health might begin prioritizing sleep or adding movement into their day. A person who values creativity might carve out a few minutes to write, paint, or build something.

In “Living With Intention,” we talked about small intentional choices such as pausing before a response, scheduling time for what matters, tidying a space to clear mental clutter. Those are exactly the kinds of acts that come alive when your values are clear. With your values guiding the way, you can select intentional actions that reflect them, making it easier to steer toward what matters rather than just reacting.

Living by your values is about nudging your life in the direction that matters to you, little by little, until those small actions add up.

A Values-Aligned Life Isn’t Always Easy

There’s a common misconception that once you know your values, everything suddenly becomes easy. In reality, living by your values can be uncomfortable.

Aligning with your values might mean saying no when you want to please others, setting boundaries, being honest when it feels vulnerable, or making choices others don’t understand. It can require sitting with discomfort, including doubt, frustration, embarrassment, or fear.

Life also gets busy. Stress piles up. Routines take over. Sometimes, disconnecting from what matters feels easier in the moment because we may simply not have the energy. So when you notice you’ve disconnected from your values, it’s important to recognize that this is normal and will happen at times.

Living a values-aligned life isn’t about perfection. It’s a practice. It’s about noticing when you drift and gently coming back.

Your Life, Guided by What Matters Most

Values help us make choices that feel meaningful and authentic, even when life feels messy. They help us notice what we care about and move toward it. Checking in with yourself regularly can be helpful:

-What mattered to you today?

-Did your choices reflect what’s important to you?

-What got in the way?

-And what small step could you take tomorrow?

Values aren’t about meeting some ideal version of yourself. They’re about being intentional. When you keep coming back to what matters most, you shape your life in a way that leads to fulfillment.

Understanding Neurodivergence and Masking: The Hidden Effort of Fitting In

Masking is a common yet often unseen experience for many neurodivergent individuals. It involves hiding or changing parts of oneself to fit in — a skill that can help in the short term but often leads to exhaustion and disconnection. This post explores what masking looks like, its emotional impact, and how caregivers and loved ones can support authenticity and self-acceptance.

Masking can feel like living with a dimmer switch turned down. Your true self is still shining underneath, just softened to fit in. For many neurodivergent people, including those with autism, ADHD, and other forms of neurodiversity, masking can serve as a short-term source of safety and belonging. Masking involves consciously or unconsciously hiding traits, stimming behaviors, or ways of thinking that might be perceived as unusual. It helps people navigate social expectations, avoid rejection, and protect against vulnerability in environments that may not yet feel accepting.

But while masking can be protective in the moment, it often comes at a cost. Over time, continually hiding parts of yourself can lead to emotional exhaustion, disconnection, and burnout. This blog explores what masking is, why it happens, and how caregivers and supports can help neurodivergent individuals feel safe turning their light back up.

What Masking Looks Like

Masking can take many forms, including:

Mimicking social behaviors such as making eye contact or mirroring gestures

Suppressing stimming behaviors like fidgeting or hand-flapping

Rehearsing conversations to appear more “typical”

Hiding challenges with attention, executive functioning, or sensory sensitivities

Why People Mask

Masking often arises from a desire to avoid judgment, bullying, or exclusion. From an early age, neurodivergent individuals may receive feedback that their natural behaviors are “wrong” or “awkward,” leading them to develop strategies to blend in. For some, masking can be a necessary coping mechanism, but for many, it becomes exhausting over time.

Why It’s Hard to Stop Masking

Even when people recognize how draining masking can be, it may feel uncomfortable or even scary to stop. Masking can become second nature after years of practice and self-protection. Many neurodivergent individuals worry about being misunderstood, rejected, or losing relationships if they begin showing more of their authentic selves.

Masking also serves an important short-term purpose. It can create a sense of safety by helping someone avoid vulnerability or emotional risk in environments that do not feel accepting. In moments where authenticity could invite criticism or harm, masking can be a protective shield that helps someone get through the day.

The challenge is that what starts as protection can become exhausting when used constantly. Over time, staying hidden can make it harder to feel seen, connected, and genuine. Unmasking takes time and gentleness. It is less about removing the mask completely and more about finding safe spaces where authenticity feels possible. Every step toward openness is an act of courage and self-trust.

What Masking Looks Like

Masking can take many forms, including:

• Mimicking social behaviors such as making eye contact or mirroring gestures

• Suppressing stimming behaviors like fidgeting or hand-flapping

• Rehearsing conversations to appear more “typical”

• Hiding challenges with attention, executive functioning, or sensory sensitivities

These are common examples of neurodivergent masking, often learned unconsciously over years of trying to adapt to expectations in school, work, or relationships.

Signs You Might Be Masking Without Realizing

Many neurodivergent people become so used to masking that it feels automatic. You might not even realize how often you’re doing it. Some common signs include:

• Feeling “on” or performative in social settings and exhausted afterward

• Replaying conversations or worrying about how you came across

• Adjusting your tone, expressions, or body language to match others

• Struggling to relax or act naturally around people outside your closest circle

• Needing long periods alone to recharge after social interactions

• Feeling unsure who you are when you’re not trying to fit in

Recognizing these patterns can be the first step toward greater self-awareness. Noticing when and where you mask can help you identify the environments that feel safe and those that require extra energy. Over time, creating neurodiversity-affirming spaces that welcome authenticity and celebrate individual differences can help reduce the need for masking and support long-term well-being.

The Cost of Masking

Consistently masking can contribute to stress, anxiety, depression, and burnout. The effort to constantly monitor and modify behavior can be mentally draining, leaving individuals feeling disconnected from their authentic selves. While masking can protect from vulnerability, it also serves as a barrier to allowing for genuine connection with others. If one is constantly masking around others, it prevents the opportunity for acceptance and authentic interactions. Many people only realize the extent of their masking later in life, often after experiencing prolonged stress or identity struggles.

Supporting Neurodivergent Individuals

Caregivers, teachers, and loved ones play a key role in noticing signs of masking. Some indicators include:

Appearing unusually tired or irritable after social interactions

Spending excessive time preparing for conversations or social situations

Experiencing physical symptoms of stress such as headaches or stomachaches

Withdrawing from activities they previously enjoyed

Acting very different in public than in private settings

Supports can help by creating safe environments where neurodivergent individuals feel comfortable expressing themselves without judgment. Encouraging small acts of authenticity, validating emotions, and offering accommodations can reduce the pressure to mask. Practical ways to do this include checking in about how social situations feel, modeling acceptance of differences, celebrating efforts to be authentic, and providing predictable routines or spaces where the individual can relax and be themselves.

Signs of Healthy Self-Expression

Healthy self-expression looks different for everyone, but may include:

Comfort in engaging in natural behaviors without shame or self-consciousness

Openly sharing thoughts, feelings, and interests with supportive people

Using coping strategies that feel sustainable rather than exhausting

Feeling a sense of relief or satisfaction after social interactions instead of burnout

The Role of Therapy in Unmasking

Therapy can be a powerful space for learning to unmask safely. A neurodiversity-affirming therapist helps clients explore the emotions tied to masking, rebuild a sense of self, and create strategies for authentic living that balance comfort and safety.

In therapy, individuals can process the stress and burnout that often accompany long-term masking. They can also practice setting boundaries, identifying triggers, and reconnecting with parts of themselves that were once hidden. Unmasking is a gradual process, and therapy offers a compassionate and safe environment for that growth.

Practical Tips for Reducing Masking

Individuals can take steps to reduce masking in daily life:

Practice small acts of authenticity, such as expressing a preference or opinion in safe settings

Create “mask-free” spaces at home, school, or work where authenticity is encouraged

Seek supportive communities where neurodivergent traits are accepted and valued

Set achievable goals for social interactions, gradually reducing the need to mask

Use mindfulness or self-affirmation to stay connected to personal feelings and needs

Embracing Neurodivergence

Awareness and acceptance of neurodivergence are crucial for reducing the pressure to mask. Environments that honor different ways of thinking, communicating, and interacting allow individuals to thrive without hiding who they are. Therapy, support groups, and advocacy can help neurodivergent individuals explore their authentic self, set boundaries, and practice self-compassion.

Moving Forward

If you notice yourself masking frequently, consider small steps toward authenticity:

Identify situations where masking is most intense

Allow yourself moments of natural behavior

Seek communities or relationships where you feel safe being yourself

Consider professional support to process the emotional impact of masking

Masking is a survival strategy, but it doesn’t have to define your life. For many neurodivergent individuals, masking has been a way to survive in a world that wasn’t built for them. Learning to unmask isn’t about flipping the lights on all at once, it’s about gently turning up the dimmer switch, one safe space and one act of authenticity at a time. With compassion, support, and self-acceptance, your true light can shine more freely, illuminating the best parts of you that’s always been there.

Why We Struggle with Communication (Even Though We Do It All the Time)

Even though we talk constantly, many of us struggle with effective communication. This blog explores the four main communication styles—passive, passive-aggressive, aggressive, and assertive—by walking through a conflict scenario and showing how each style plays out. It highlights the role of empathy, the importance of boundaries, and the balance between being direct and kind (drawing on DBT interpersonal effectiveness skills). It also discusses the limits of technology in conversations and why self-empathy matters just as much as empathy for others. Practical tools like a simple boundary-setting script, reflection questions, and exercises make the post actionable for readers who want to strengthen their relationships.

We talk every day, sometimes nonstop. Conversations with coworkers, friends, partners, family, even quick exchanges with strangers. Yet despite all this practice, many of us aren’t actually very good at communicating effectively. We stumble, misinterpret, over-explain, avoid, or escalate without realizing it. Good communication is a skill, not something that comes automatically.

Different Communication Styles

Most people lean into one of four main communication styles. Understanding them can help us notice our own patterns, and the patterns of others:

Passive – Avoids conflict at all costs, often staying silent even when feelings are hurt. Short-term peace, but long-term resentment builds.

Passive-Aggressive – Pretends everything is fine on the surface while expressing frustration indirectly (sarcasm, guilt-trips, the silent treatment). Creates confusion and mistrust.

Aggressive – Speaks loudly, forcefully, and sometimes disrespectfully. Gets the point across, but often damages relationships.

Assertive – Communicates directly, respectfully, and with clarity. Balances honesty with empathy. Assertive communication tends to lead to the healthiest and most sustainable outcomes.

One Conflict, Four Styles

Imagine this scenario: A friend cancels plans last minute, and your feelings are hurt. Here’s how the conversation might play out depending on your style—and how the other person may respond.

Passive

You: “It’s fine, don’t worry about it.”

Friend: Relieved and moves on, assuming you’re not upset. Meanwhile, your hurt feelings remain unspoken.

Passive-Aggressive

You: “Wow, must be nice to have so much free time to cancel on people.”

Friend: Feels confused or defensive. They may think, “Are they mad at me or joking?” The relationship tension lingers without clarity.

Aggressive

You: “You’re so unreliable! You clearly don’t care about me.”

Friend: Likely to become defensive or angry, firing back or shutting down. The focus shifts from your hurt to a bigger argument.

Assertive

You: “I felt hurt when you canceled at the last minute. I understand things come up, but I’d appreciate more notice next time.”

Friend: More likely to apologize and explain, without feeling attacked. This response leaves space for understanding, repair, and moving forward.

This highlights something important: the way we speak often shapes how the other person responds. Our tone and delivery can either open the door to connection or shut it down.

Empathy: The Core of Connection

Empathy isn’t just about being nice—it’s a skill set. Brené Brown describes four essential parts of empathy:

Perspective Taking – Seeing the situation from the other person’s viewpoint.

Staying Out of Judgment – Resisting the urge to criticize or evaluate their feelings.

Recognizing Emotion – Identifying what they’re experiencing.

Communicating Recognition – Letting them know they’ve been heard and understood.

Empathy is powerful because it says, “I’m willing to sit with you in this emotion without fixing, minimizing, or blaming.”

Why Empathy Feels Hard

Empathy requires vulnerability. To connect with someone’s sadness, fear, or frustration, we often have to touch those same emotions within ourselves. That’s uncomfortable, which is why we sometimes default to advice, distraction, or blame.

And here’s a common fear: “If I focus on their feelings, does that mean I’m dismissing mine?” But empathy doesn’t erase your needs. It simply acknowledges the other person’s emotional reality. The balance comes in pairing empathy with boundaries.

Boundaries: Empathy With Self-Respect

A healthy boundary is a way of saying, “I can care about how you feel, and I can still care about my own needs.”

For example:

Empathy without boundaries might sound like: “I understand you were stressed, so I’ll just let it go, even though I’m still hurt.” (Leads to resentment.)

A boundary with empathy might sound like: “I get that you had a lot going on. At the same time, I still felt hurt. I’d like us to find a better way to handle this next time.”

Boundaries are not walls. They’re guidelines for people around us to maintain healthy connections with us. When paired with empathy, they prevent burnout, resentment, and people-pleasing.

A Simple Script for Setting Boundaries

Boundaries don’t have to be complicated. A helpful framework is:

“When X (neutral event) happens, I feel Y (emotion), and I need Z (positive need).”

This structure keeps the focus on your feelings and needs rather than blame or criticism. It’s important to remember that we communicate our need in a way that is actionable for the other person. Often, we’re quick to focus on the negative behavior—what we don’t want—however when we do that, we lose sight of clearly communicating the behavior we do want to see moving forward.

Examples:

Friendship: “When plans get canceled last minute (X), I feel hurt and unimportant (Y). I need more notice if things change (Z).”

Work: “When meetings run late without warning (X), I feel stressed and overwhelmed (Y). I need to know in advance if we’ll go over time (Z).”

Family: “When my privacy isn’t respected (X), I feel frustrated (Y). I need some quiet time in the evenings to recharge (Z).”

Using this approach helps you stay assertive, empathetic, and clear—without over-explaining, drifting into aggression, or avoiding the conversation altogether. It centers your needs while giving the other person a clear path to respond positively.

The Blame Game

Brené Brown often describes blame as “a way to discharge discomfort and pain.” When something goes wrong, our minds want a target — someone or something to point to — because blame gives the illusion of control. It feels easier to say, “This is your fault,” than to sit with the discomfort of hurt, disappointment, or vulnerability.

But when we focus on blame, we step away from accountability and lose sight of what actually matters — our feelings and needs in the situation. Instead of identifying, “I felt hurt when that happened,” or “I needed to feel understood,” blame pushes us into defense mode.

Once blame enters the conversation, defensiveness quickly follows. The other person stops listening because they’re busy protecting themselves. We stop listening because we’re focused on being right. The conversation shifts from repair to combat, and the original issue — the hurt, misunderstanding, or unmet need — gets buried under a tug-of-war over who’s at fault.

Blame also keeps us from genuine self-reflection. It becomes the opposite of accountability:

Accountability says, “Here’s my part, and I’m willing to own it.”

Blame says, “This isn’t my fault, and I won’t change.”

The goal isn’t to avoid responsibility — it’s to stay curious and compassionate. Instead of, “Who’s to blame?” we can ask, “What happened here?” or “What was I feeling in that moment?”

This shift opens space for empathy and understanding, allowing both people to move toward resolution rather than staying trapped in reaction.

Why We Over-Explain (and Why Less Is More)

When we’re anxious about being misunderstood or fear disappointing someone, we often start over-explaining: adding more words, more context, and more apologies. Deep down, it’s usually an attempt to manage other people’s emotions or control how they perceive us.

But over-explaining often backfires. The more we talk, the more the message gets lost. Instead of clarity, we create confusion or defensiveness.

Over-explaining sounds like:

“I’m sorry, I didn’t mean it like that, I just thought maybe if you had time — but it’s totally fine if you don’t!”

It can come from a place of people-pleasing or fear of rejection. We hope that by softening or over-qualifying our message, we’ll avoid conflict. But in reality, it dilutes our needs and boundaries.

Less is more. A clear, calm statement is more likely to be heard than a long, anxious one.

Try this shift:

Instead of: “I’m sorry, I know you’re busy, but it just kind of hurt when you didn’t reply. I totally get it though, I know you have a lot going on.”

Say: “I felt hurt when I didn’t hear back. Is everything okay between us?”

Directness feels uncomfortable at first because it is more vulnerable, however it communicates self-respect and empathy in two sentences.

Technology: A Blessing and a Barrier

Technology makes staying connected easier than ever. A quick text can confirm plans, check in on a loved one, or share encouragement in seconds. Video calls allow us to see the faces of friends and family across the world. Social media keeps us updated on people’s lives even when distance separates us.

But there’s a downside: over-reliance on technology can weaken real communication. Tone gets lost in text. Emojis and punctuation can be misread. Silence can feel like rejection. And sometimes, hiding behind a screen feels safer than having a vulnerable, honest conversation face-to-face.

Another risk is that relationships can get stuck at a surface level. It’s easy to “like” a post, send an emoji, or fire off a quick text—but those interactions don’t always deepen trust or understanding. They give the appearance of connection without the substance. True connection often requires slowing down, listening, and being present with someone’s full emotional experience—something much harder to capture in a short digital exchange.

Technology works best as a support, not a replacement. It’s great for convenience, but meaningful conversations often need more—our voices, facial expressions, and presence. Sometimes the best way to resolve conflict or express care is still the old-fashioned way: talking in person or picking up the phone.

Start With Self-Empathy

One piece often overlooked: how we talk to ourselves. If your inner dialogue is harsh—“I’m stupid, I always mess this up”—it’s harder to speak kindly and assertively with others. The way we communicate externally often mirrors the way we communicate internally.

Self-empathy means extending the same compassion and understanding towards yourself that you’d naturally offer a friend. Instead of criticizing yourself for mistakes, you pause to acknowledge your feelings with curiosity and care.

Recognize what you feel – “I’m anxious right now.”

Validate the emotion – “It makes sense I feel this way after that conversation.”

Offer kindness instead of judgment – “I’m learning, and it’s okay not to have this perfect.”

Something important to emphasize here is that self-empathy is not self-pity. It doesn’t mean excusing harmful choices or avoiding accountability. Instead, it provides the emotional safety net that allows you to grow and change without shame.

And just like with others, self-empathy pairs best with boundaries. You can be gentle with yourself and hold yourself accountable:

“I didn’t communicate clearly this time. That doesn’t make me a failure, and I’ll practice being more direct next time.”

When we strengthen our capacity for self-empathy, we become less reactive and more grounded. That steadiness makes it easier to communicate with others in a way that is both compassionate and assertive.

Try This: A Quick Skill-Building Practice

You don’t need a big workbook to start practicing—just a few intentional steps can make a big difference.

Think of a recent conflict or miscommunication.

Write out what you actually said.

Then rewrite it in an assertive + empathetic format, using the “When X, I feel Y, I need Z” script.

Optional: practice saying it out loud in front of a mirror.

This simple exercise can help build confidence in communicating more clearly and effectively. After practicing, notice how the conversation feels. Did you come across clearer? Did the other person respond differently? Communication is a skill, and progress comes from reflection and repetition, not perfection.

Takeaway

We all talk, but talking isn’t the same as communicating effectively. Becoming aware of your communication style, practicing empathy (for yourself and others), setting boundaries, and leaning into clear, assertive expression can strengthen your relationships.

And remember: the way you communicate shapes how the other person responds. Blame builds walls. Empathy builds bridges. Boundaries keep the bridge safe and sturdy. Say less when you can, listen more, and keep it genuine.

Reflection Questions

Which communication style do I use most often—passive, passive-aggressive, aggressive, or assertive?

How does my communication style influence how others respond to me?

When was the last time empathy helped me connect with someone?

Where might I need to pair empathy with stronger boundaries?

How do I speak to myself—and how does that affect how I speak to others?

OCD vs. Anxiety: Why the Difference Matters

OCD is often mistaken for generalized anxiety, which can lead to misdiagnosis and treatment that doesn’t fully address the root problem. This blog explores the key differences between OCD and anxiety, highlights how OCD symptoms can show up in less visible ways (like Pure O and internal compulsions), and explains why recognizing OCD subtypes matters—even though they aren’t formally listed in the DSM-5. We also discuss treatment options beyond ERP, including CBT, ACT, and medication, while offering practical tips for loved ones to support someone with OCD without falling into reassurance cycles.

Alex had been struggling for years with constant worry that he wasn’t being productive enough. He would spend hours mentally reviewing tasks, repeatedly checking his work, and feeling tense and anxious. He sought treatment for anxiety, but while therapy helped him manage some stress, the underlying distress didn’t go away. What was missing? Alex actually had OCD, and his intrusive thoughts and mental rituals required specialized treatment.

Many people like Alex are misdiagnosed because OCD symptoms, such as repetitive worries, intrusive thoughts, or mental checking, can look a lot like generalized anxiety. This can lead to treatments that address only the surface anxiety, leaving the obsessive-compulsive cycle intact. Understanding the difference between OCD and anxiety is crucial to getting the right care and support.

The Scope and Impact of OCD

OCD is more common than many realize, affecting about 2–3% of the population worldwide. Unfortunately, research shows it can take an average of 7–10 years from the onset of symptoms for someone to receive the correct diagnosis and treatment. In that time, OCD can interfere with school, work, relationships, and quality of life.

Why OCD Is Often Missed as a Diagnosis

OCD and anxiety share many similarities. Both involve intense worry, fear, and physical symptoms like restlessness or racing thoughts. What makes OCD different is the presence of obsessions (intrusive, unwanted thoughts or images) and compulsions (behaviors or mental rituals done to reduce distress).

Because the anxiety caused by OCD is so strong, many people (and even clinicians) may focus only on the anxiety symptoms, overlooking the underlying obsessive-compulsive cycle. This can lead to a diagnosis of “generalized anxiety” without recognizing that the core issue is OCD. Missing the diagnosis often delays access to the specific treatments.

The Shame and Stigma Factor

One of the biggest reasons OCD goes unnoticed is shame. People often fear judgment for their intrusive thoughts—especially when those thoughts are violent, sexual, or go against their values. Misunderstandings like “we’re all a little OCD” trivialize the condition, making it harder for people to open up. The secrecy fueled by shame delays help, allowing symptoms to grow stronger over time.

Breaking this stigma is critical. Talking openly about the wide range of OCD presentations helps normalize the experience and reminds people that intrusive thoughts do not reflect character or intent.

A Closer Look: OCD vs. Anxiety in Action

To understand the difference, let’s compare two scenarios:

Anxiety example: Someone may worry about forgetting to lock the door before leaving for work. They might briefly double-check, then go about their day still carrying some unease.

OCD example: Someone with OCD may feel overwhelmed by an intrusive fear that if they don’t lock the door just right, something terrible will happen. To quiet the distress, they may check the lock dozens of times, replay memories to “make sure,” or even avoid leaving home altogether.

Both involve worry, but OCD creates a cycle of obsessions and compulsions that can consume hours of the day and significantly disrupt life.

Subtypes of OCD and Why They Matter

Even though the DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) doesn’t officially break OCD into categories, many clinicians and people with lived experience talk about different “subtypes.” You might hear that there are around 18 themes, like contamination, checking, harm, scrupulosity, relationship OCD, or Pure O.

The reason the DSM-5 doesn’t separate them is because the underlying cycle of OCD (obsessions leading to compulsions) is the same no matter the theme. Whether someone is washing their hands dozens of times or replaying a thought in their mind, the brain process is similar.

Still, talking about subtypes can be really useful. It helps people realize they’re not alone or “weird” for the kinds of thoughts they have, and it gives language to something that often feels isolating. It also helps therapists shape treatment in a way that fits.

So while subtypes aren’t official in the diagnostic manual, they’re still important to recognize. They make the experience of OCD more understandable, and they remind people that their symptoms are valid.

More Recognized Subtypes of OCD

OCD doesn’t look the same for everyone. Subtypes describe common themes obsessions and compulsions may take, but it’s important to remember that OCD can attach itself to almost any area of life. Here are some of the more recognized subtypes:

Contamination OCD: Intense fears of germs, illness, or unclean environments. Compulsions often include excessive washing, cleaning, or avoiding certain places or people.

Checking OCD: Repeatedly checking things—locks, appliances, emails, or even memories—to relieve fears of causing harm or making a mistake.

Harm OCD: Intrusive thoughts of accidentally or intentionally hurting oneself or others. These thoughts are distressing and unwanted, often leading to avoidance or mental rituals for reassurance.

Religious or Scrupulosity OCD: Obsessions centered on morality, blasphemy, or offending a higher power. Compulsions might include excessive praying, confession, or seeking reassurance about being “good enough.”

Sexual or Relationship OCD: Disturbing intrusive thoughts about sexuality, fidelity, or attraction. Compulsions may involve seeking reassurance, avoiding intimacy, or mentally analyzing feelings.

Symmetry and Ordering OCD: A need for things to feel “just right.” This might involve arranging objects symmetrically or repeating actions until they feel correct.

Sensorimotor (Somatic) OCD: Persistent awareness of automatic bodily functions such as breathing that can lead to hypervigilance

What About “Pure O”?

Another term that often comes up is Pure O, short for “purely obsessional OCD.” Many people with OCD describe experiencing only obsessions—distressing intrusive thoughts, images, or doubts—without the visible, outward compulsions like handwashing or checking.

It’s important to note, however, that Pure O doesn’t mean there are no compulsions at all. Instead, the compulsions are often internal or mental, making them harder to spot. For example, someone may silently repeat phrases, pray, review past events for reassurance, or mentally check whether they felt the “right” emotion. These hidden rituals provide temporary relief but keep the OCD cycle going.

Because these compulsions aren’t obvious, Pure O is especially likely to be mistaken for anxiety or rumination. This makes awareness crucial: intrusive thoughts alone don’t define OCD. It’s the cycle of obsessions and compulsions, whether visible or invisible, that makes it OCD.

OCD as a Spectrum

Another key point is that OCD exists on a spectrum. Someone may primarily struggle with one theme, such as contamination fears, but later develop obsessions in a completely different area, such as relationships or morality. Shifts in themes over time are common, and many people live with multiple subtypes at once. Recognizing OCD as a spectrum helps us understand that it isn’t limited to one “look” or set of behaviors.

For Loved Ones: How to Support Someone with OCD

Supporting a loved one with OCD can feel confusing—you want to ease their distress, but sometimes reassurance or accommodation can unintentionally reinforce the OCD cycle. Here are some ways to show care without fueling symptoms:

Educate Yourself: Learning the basics of OCD helps you separate your loved one’s values and personality from the intrusive thoughts they struggle with. OCD is not a choice, and the compulsions are driven by real distress.

Offer Compassion, Not Reassurance: Constant reassurance (“You’re fine, you did enough today”) can actually strengthen OCD’s grip, because it trains the brain to rely on others for temporary relief. Instead, try validating the feeling without confirming or denying the worry:

Instead of: “Don’t worry, you were really productive today.”

Try: “I can see how stressful those thoughts about productivity feel. I believe you’re working hard on handling them.”

Set Healthy Boundaries: Boundaries aren’t about withholding love—they’re about creating balance and protecting both people’s well-being. Examples might include:

“I care about you, but I can’t keep checking your to-do list every night. I’ll cheer you on while you practice trusting yourself instead.”

“I won’t be able to answer the same productivity question over and over, but I’m happy to sit with you while you ride out the anxiety.”

“I love you, and I want to support your therapy homework instead of doing the rituals for you.”

Encourage Professional Help: ERP is considered the gold standard for OCD treatment, but it’s not the only approach. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), and medication can also be part of effective treatment. Sometimes a combination provides the best outcome.

Support Progress, Not Perfection: Recovery from OCD isn’t linear. There will be setbacks, and that’s normal. Offer encouragement when your loved one tries something hard, rather than focusing only on the outcome.

Important Reminder: You don’t have to become your loved one’s therapist. Your role is to provide steady support, encouragement, and boundaries that honor both their recovery journey and your own well-being.

Closing Thoughts

OCD can be overwhelming, isolating, and misunderstood—but it is also highly treatable. Recognizing the difference between anxiety and OCD is a powerful first step toward the right kind of help. With evidence-based therapies, support from loved ones, and compassion for the journey, recovery is possible.

If you’re supporting someone with OCD, remember: you don’t need all the answers. What matters most is patience, empathy, and setting boundaries that protect both of you. And if you’re the one living with OCD, know that your intrusive thoughts are not a reflection of who you are, they are a symptom of a disorder that you can learn to manage.

There is hope, and there are tools. While healing doesn’t mean eliminating every intrusive thought. Healing does mean learning to live fully without letting OCD call the shots. You are not alone, and with the right help, you can start connecting back to things that matter to you in life.

References & Resources

International OCD Foundation (IOCDF): https://iocdf.org

Offers education, research updates, and a provider directory for specialized OCD treatment.National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH): https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/obsessive-compulsive-disorder-ocd

Provides an overview of OCD, symptoms, and treatment options.Anxiety & Depression Association of America (ADAA): https://adaa.org

Includes resources on OCD, anxiety, and evidence-based treatment approaches.Books:

Freedom from Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder by Jonathan Grayson, PhD

The Mindfulness Workbook for OCD by Jon Hershfield, MFT, & Tom Corboy, MFT

Overcoming Unwanted Intrusive Thoughts by Sally Winston, PsyD, & Martin Seif, PhD

OCD Unlocked: A Teen’s Workbook for Understanding and Thriving with OCD by Lillian Carlyle

The OCD Breakthrough Series (3 books) | by Cross Border Books

If you or someone you love is struggling, reaching out to a licensed mental health professional trained in OCD treatment is an important first step.

The Stages of Change: Why We Struggle to Follow Through (and How to Keep Moving Forward)

Change isn’t a straight line—it’s a process. The stages of change model reminds us that we move through phases like contemplation, planning, action, and maintenance, with the possibility of setbacks at any stage. Using the Passengers on the Bus metaphor from ACT, this blog explores why it’s so easy to slip back into old routines (like skipping the gym or abandoning new habits) and how values can guide us toward long-term change. Whether you’re working on your own growth or supporting someone else, understanding the stages of change helps us meet ourselves—and others—with more compassion and direction.

January rolls around, and suddenly the gym is packed. By March, the parking lot is empty again. Most of us know this pattern well. We set out with good intentions—going to the gym, eating better, saving money, or cutting back on social media—but the excitement fades, life gets in the way, and we slip back into old habits.

It’s not because we’re lazy or incapable. It’s because change isn’t a one-time decision—it’s a cycle. And understanding that cycle helps us stick with what matters and extend compassion to ourselves (and others) when we stumble.

The Five Stages of Change

1. Precontemplation – Not Yet Considering Change

Here, the idea of change isn’t even on our radar. Maybe we’ve thought, “I should probably exercise more,” but it doesn’t feel urgent or realistic.

Example: The gym shoes are buried in the closet. Friends invite you to join them for a class, but you shake your head—you’re not there yet.

2. Contemplation – Weighing Pros and Cons

This is the “thinking about it” stage. You know change might be helpful, but the barriers feel heavy.

“I’d feel healthier if I worked out… but I’m exhausted after work.”

“I want to save money… but online shopping is so easy.”

It’s common to stay here a while. Ambivalence is part of the process, not a flaw.

3. Preparation (Planning) – Setting Intentions

At this stage, we begin taking small steps: signing up for a gym membership, downloading a budgeting app, or putting our phone in another room before bed. We’re building readiness, but we haven’t built consistency yet.

The challenge? Sometimes planning feels like progress, and we mistake preparation for action.

4. Action – Doing the Thing

This is when change starts to happen. You’re going to the gym, tracking your spending, or sticking with a nighttime routine. Momentum builds—but so does resistance.

You might feel the pull of excuses, old patterns, or passengers on the bus (we’ll get to that in a moment). Motivation can spark the action stage, but habits keep it alive.

5. Maintenance – Stabilizing the Habit

Here, the change feels more natural. The gym is a regular part of your week. Saving money has become a rhythm. Screen time is more intentional.

Relapse

Relapse—sliding back into old patterns—can happen at any stage. A stressful week, travel, or illness might derail progress. It is important to normalize that relapse isn’t failure. It’s just part of the cycle.

Think about what it takes to build a new car. No company would release the very first prototype and expect it to be perfect. Engineers test, adjust, and rework the design over and over until it’s safe, reliable, and road-ready.

Change works the same way. Your first attempt at a new habit—whether it’s exercising, budgeting, or setting boundaries—probably won’t be flawless. You might stall, take a detour, or even go back to old patterns for a while. That doesn’t mean the change “failed.” It just means you’re still refining the model.

Relapse isn’t the end of the journey—it’s part of the testing process. Each time you return to the drawing board, you’re learning what works and what doesn’t, making it more likely that your “final version” will actually last.

Why We Lose Momentum

So why do we start strong and then stall?

Vague goals: “I’ll eat healthier” is hard to measure or sustain.

Loss of motivation: The spark fades, and life feels too busy.

Expectations about speed: We hope new habits stick in weeks, but research suggests it can take 2–12 months before a behavior feels automatic.

Discomfort: If change was easy, we would just do it. Real change is uncomfortable physically, emotionally or both. Change means we have to be okay with stepping outside our comfort zone and staying there for a while.

All-or-nothing thinking – Missing one workout, overspending once, or slipping up with a boundary doesn’t mean you’ve failed. But if we believe a misstep equals failure, we’re more likely to give up altogether.

This is why patience—and seeing ourselves through the stages of change—really matters. Building lasting change isn’t about speed; it’s about endurance. Think of it less like a sprint and more like training for a marathon. Setbacks are part of the process. What counts most isn’t whether you stumble, but how you respond: noticing when you’ve veered off course, choosing to regroup, and gently steering yourself back toward your values.

The Passengers on the Bus

A metaphor I often share is called Passengers on the Bus, from Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT).

Imagine you’re the driver of a bus, following a familiar route. This route represents our daily routines—wake up, go to work, come home, go to sleep, repeat. Ideally, we want our bus to head in the direction of our values—things like health, balance, freedom, or connection. But sometimes, we realize that parts of our route no longer serve us, that is starting to disconnect us from our goals and values and that’s when we start thinking about change.

The passengers on the bus are your thoughts, feelings, and habits. They shout things like:

“You’re too tired today.”

“You’ll never stick with this.”

“It’s easier to do what you’ve always done.”

Often, we let these passengers steer us back onto the old, familiar route. It feels safe because we’ve driven it so many times before—we know the shortcuts, the potholes, ways to avoid the detours. But that comfort doesn’t mean it takes us where we want to go.

The goal isn’t to kick the passengers off (you can’t). The goal is to stay in the driver’s seat and keep steering toward what matters, even with their noise in the background. Your values are the compass that remind you why the route is worth it.

Practical Tips for Each Stage

Precontemplation: Focus on curiosity, not pressure. Ask yourself, “What might be different if I did make a change?”

Contemplation: Write out your pros and cons. Notice how your reasons for change connect with your values.

Preparation: Get specific. Not “exercise more,” but “walk 20 minutes after dinner three times a week.”

Action: Pair new habits with existing routines (change clothes after work, head straight to the gym). Build accountability—share your goal with a friend.

Maintenance: Create supports for the long haul. Celebrate milestones and track progress. Expect setbacks and have a plan to restart gently.

Relapse: Ask, “What pulled me off track? What small step will get me back on?” Think adjustment, not starting over.

Why Knowing the Stages Matters

Understanding your own stage helps you set realistic expectations and show yourself compassion when things don’t go perfectly. Knowing what stage you are in allows for you to:

Reduce shame – If you’re still in contemplation but expect yourself to be in action, you’ll feel like you’re failing. Recognizing your actual stage normalizes why you might not be ready to take big steps yet.

Match strategies to readiness – Different stages need different approaches. Someone in planning benefits from setting specific goals, while someone in precontemplation needs reflection and awareness first.

Build patience – Change isn’t just about “trying harder.” By seeing it as a process, you understand that setbacks are expected, not proof that you can’t change.

Help us support others – Knowing the stages also helps us meet friends, clients, or loved ones where they are, instead of pushing them ahead too quickly.

In short, knowing your stage gives you a map. Without that map, it’s easy to get lost in self-criticism or use strategies that don’t fit. With it, you can walk the path of change step by step, with more clarity and self-compassion.

Why This Matters for Supporting Others

Change is deeply personal, but it doesn’t happen in isolation. Recognizing the stages of change also helps us understand where others are. If a loved one isn’t ready for action, pushing harder won’t help—it can actually make them dig in more. This perspective can help reduce our frustration when someone isn’t “changing fast enough” and helps us set realistic expectations for their progress. Meeting people where they are, with empathy, makes change safer, more possible and allows us to stay healthy supports without burning ourselves out.

Final Takeaway

Change is rarely a straight line—it’s a cycle of progress, setbacks, and learning. By understanding the stages of change, we can meet ourselves (and others) with more patience, realistic expectations, and compassion. Whether you’re in contemplation, action, or somewhere in between, every step matters because it brings you closer to living in alignment with your values.

To take this from theory into practice, here are a few questions to reflect on:

Which stage of change am I in right now for the goal I’m working on?

What values matter most to me, and how does this goal connect with them?

What “passengers on the bus” (thoughts, feelings, or habits) tend to pull me back to the old route?

When I’ve relapsed in the past, what patterns or triggers showed up? What can I learn from them?

What’s one small, specific step I could take this week to move from my current stage toward the next?

If I’m supporting someone else, how can recognizing their stage reduce my frustration and help me set more realistic expectations for their progress?

What would self-compassion look like as I move through these stages?

Remember: the goal isn’t perfection—it’s persistence. Each loop through the cycle builds resilience, wisdom, and strength. Stay in the driver’s seat, keep your values as your compass, and allow yourself to keep moving toward what matters most.

Supporting a Loved One With an Eating Disorder

Supporting someone with an eating disorder (ED) can feel overwhelming, but your love, patience, and presence are powerful tools in their recovery. Eating disorders are serious mental health conditions—not a choice—and often serve as maladaptive coping mechanisms. They can be isolating, and recovery may uncover underlying struggles like anxiety, trauma, or depression.

When someone you love is struggling with an eating disorder, it can be painful to watch. You may feel helpless, unsure of what to say, or afraid of making things worse. Your presence, patience, and compassion are incredibly powerful. While eating disorders are complex mental health conditions that require professional support, loved ones play an essential role in the recovery journey.

Understanding Eating Disorders

Eating disorders affect nearly 30 million Americans at some point in their lifetime. They are not just about food or appearance—they are serious mental health conditions influenced by genetics, environment, trauma, and cultural pressures. Eating disorders have the second highest mortality rate of any mental health disorder (after opioid use disorder).

It’s also important to distinguish between disordered eating and a clinically diagnosed eating disorder. Disordered eating may include behaviors like skipping meals, chronic dieting, or rigid food rules, however an eating disorder typically involves more severe and persistent patterns that interfere with daily life, relationships, and health. Both deserve compassion and can benefit from support, and a diagnosed eating disorder often requires specialized treatment.

Eating disorders can also feel incredibly isolating. Many people withdraw from friends, family, and activities they once enjoyed. Reminding your loved one that they are valued beyond their illness—and that they don’t have to go through this alone—can help bridge that isolation.

Warning Signs to Look Out For

It can sometimes be hard to recognize when someone is struggling. Remember eating disorders are isolating and secretive by nature. A few potential red flags include:

Skipping meals or making excuses not to eat

Dramatic changes in weight (up or down)

Preoccupation with calories, weight, or body size

Avoiding social situations involving food

Excessive exercise or distress when exercise is interrupted

Rigid food rules (e.g., labeling foods “good” or “bad”)

Withdrawal from friends or activities

Extreme perfectionism or heightened anxiety around eating

Not every sign points to an eating disorder, but noticing patterns can help you gently open conversations and encourage professional support.

Myths & Misconceptions About Eating Disorders

Despite growing awareness, many misconceptions about eating disorders remain. Clearing them up is an important step toward reducing stigma and offering compassionate support.

Myth: Eating disorders are a choice.

Reality: No one would choose the pain, medical risks, and isolation that come with an eating disorder. They are serious mental health conditions—not diets gone too far or vanity projects.

Myth: Eating disorders are just about food or wanting to be thin.

Reality: Eating disorders often start out as maladaptive coping mechanisms—ways of managing overwhelming emotions, trauma, or stress. Food and body image become the focus, but underneath, the disorder may be helping someone feel in control, numb, or distracted from deeper pain.

Myth: Once someone stops the behaviors, they’re “better.”

Reality: Recovery involves peeling back the eating disorder behaviors, but when those are stripped away, underlying issues like anxiety, depression, or trauma often come forward. This is why professional treatment and ongoing support are so essential.

Myth: Only young, thin, white women struggle with eating disorders.

Reality: Eating disorders affect people of all genders, ages, races, body sizes, and backgrounds. Weight stigma and cultural bias often prevent people in larger bodies, men, or people of color from being recognized and treated.

Why Early Intervention Matters

The earlier someone receives support, the better the chances for full recovery. Waiting until “things get worse” can allow the disorder to become more entrenched. Even if you’re unsure whether your loved one’s behaviors are “serious enough,” it’s better to seek help sooner rather than later.

Medical Risks to Be Aware Of

Eating disorders can affect nearly every system in the body, including:

Heart health (arrhythmias, cardiac arrest)

Bone density (osteopenia, osteoporosis)

Fertility and hormones (menstrual changes, low testosterone)

Digestive health (slow motility, bloating, reflux)

Brain health (difficulty concentrating, mood instability)

These risks highlight why eating disorders need specialized medical and mental health care—not just willpower or lifestyle changes.

Treatment and the Team Approach

Effective treatment often involves a multidisciplinary team, ideally with each member specializing in eating disorders. A well-rounded team may include:

Therapist – using approaches like CBT-E, DBT, ACT, FBT, or trauma-informed therapy

Dietitian – trained in eating disorders, weight-inclusive care, and nutrition therapy

Physician or pediatrician – monitoring medical stability and complications

Psychiatrist – addressing co-occurring mental health conditions and medication needs

Why specialization matters: Not all providers are trained in eating disorders. Working with professionals who don’t specialize can sometimes be damaging—for example, if a provider emphasizes weight loss, uses diet culture language, or overlooks serious medical risks. A specialized team is better equipped to treat the whole person, not just the behaviors.

Having a professional treatment team also allows you to remain in the role of loved one—not dietitian or therapist role. This matters because sometimes the eating disorder resists or even lashes out against support. By trusting the professionals to guide treatment, you can focus on being a consistent, compassionate presence in your loved one’s life.

How You Can Help

1. Lead with compassion, not criticism

It can be tempting to reassure with comments about weight or eating (“you look healthy,” “just eat more”), but these often backfire. Instead, focus on expressing care:

“I love you and I’m here to support you.”

“I may not fully understand, but I want to be here for you.”

When commenting on appearance, shift the focus from body size to mood or energy:

Instead of “You look great,” try “You look really happy today.”

Instead of “You’ve lost/gained weight,” try “It’s so nice to see you enjoying yourself.”

2. Separate the person from the eating disorder

Your loved one is not their illness. It can help to think of the eating disorder as an external force that is influencing them, rather than who they are at their core. This perspective allows you to direct frustration toward the disorder, not your loved one, and remind them of their strengths outside of food, weight, or body image.

3. Think about your own language around food and body image

Comments like “I feel so fat” or “I need to burn this off” may seem harmless but can reinforce harmful thought patterns. Try to model neutral or positive language around food and body image. Celebrate what bodies can do rather than how they look, and talk about food as nourishment rather than something to earn or restrict.

4. Listen more than you speak

You don’t need to have the “right” words. Often, simply listening with openness and compassion is more healing than offering advice. Focus on creating a safe space where your loved one can share what feels comfortable. Show empathy by validating their feelings while still separating them from the eating disorder.

Example: Instead of saying “Just eat, you’ll feel better,” you might say, “I know eating feels really hard right now. Let me know how to support you.”

5. Do’s and Don’ts for Loved Ones

6. Educate yourself

Understanding the medical and emotional complexities of eating disorders can help you respond with empathy. Additionally, understanding systemic barriers to care is important. LGBTQ+ folks, BIPOC individuals, and those in larger bodies often face unique stigma and discrimination in accessing treatment. Pointing your loved one toward affirming, inclusive resources can make a difference. These resources can guide you:

National Eating Disorders Association (NEDA) – nationaleatingdisorders.org

National Alliance for Eating Disorders – allianceforeatingdisorders.com

The Trevor Project (for LGBTQ+ youth) – thetrevorproject.org

Health at Every Size (HAES) – Association for Size Diversity and Health

Books like Health at Every Size by Lindo Bacon, PhD, and Body Respect by Lindo Bacon & Lucy Aphramor

HAES promotes dignity, respect, and access to care for people of all body sizes. This framework helps challenge diet culture and weight stigma—two powerful risk factors that can fuel eating disorders.

7. Encourage professional help—gently

Eating disorders rarely resolve on their own. You can encourage your loved one to reach out for professional care, but avoid ultimatums. Sometimes offering to help research providers or go with them to an appointment can lower barriers.

8. Support daily life in practical ways

Eating disorders can make everyday situations (meals, social events, even doctor’s visits) overwhelming. Offering to sit with them during meals, provide distractions, or just be a grounding presence can help reduce isolation.

9. Take care of yourself, too

It’s common for caregivers to feel exhausted or even burnt out. Seeking your own support—whether therapy, a support group, or leaning on friends—allows you to keep showing up in a sustainable way.

10. Remember that recovery is not linear

Relapses and lapses can happen. Try not to see them as failures, but as part of the recovery process. Acknowledge the effort your loved one is putting in and celebrate even small steps forward.

When Your Loved One Isn’t Ready to Challenge Their Eating Disorder